Diligent Sunday Newsletter / Issue #11 about Financial Stability

Discover how I transitioned from a spending power mindset to capital thinking for financial success. Key strategies include dodging debt, stock market investments, and debunking financial fallacies. Utilize tools like the 50/30/20 rule, budgeting, and savings forecasts to attain financial stability.

Dear Diligent Sunday Readers,

And another week has passed. As of today, 23.1% of the year has elapsed, and the quarter is ending soon. In my home country, the clocks were set forward for daylight saving time, and a 5 am Miracle Morning becomes a 4 am Groggy Morning.

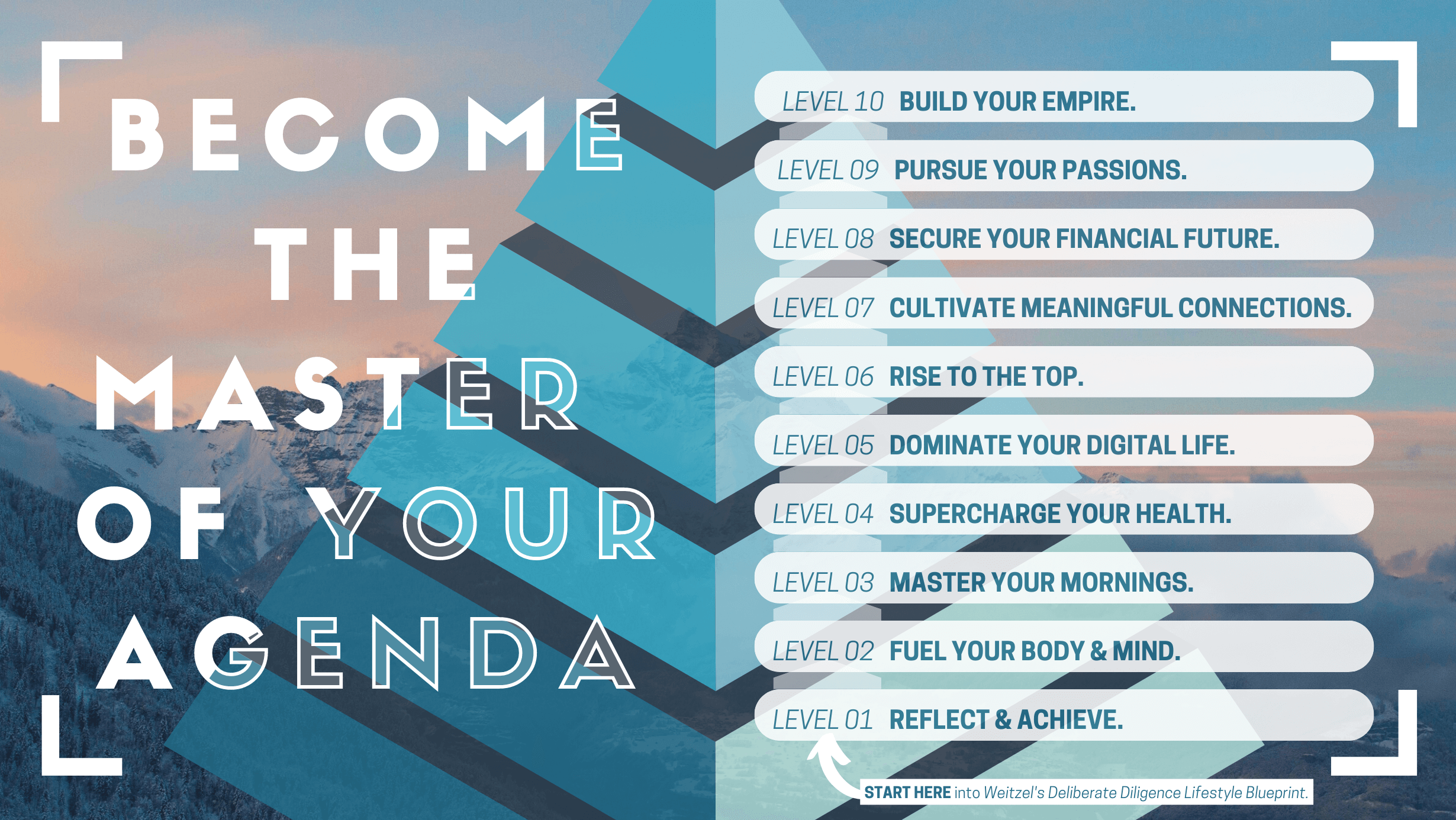

But today, I don't want to discuss productivity in this newsletter but financial stability. As you know, this is the 8th level of the Deliberate Diligence Lifestyle Blueprint.

I've noticed that in the 80 blog articles I've written since the end of September, I've only written about this area twice.

The reason is that I see finances more as a hygiene factor and that I believe prosperity will more or less automatically come with Deliberate Diligence, as a society will reward you for your efforts. Accordingly, I rarely think about this area of my life.

However, it is true that in my early 20s, I had some mindset mistakes that almost drove me to financial ruin. So, it's reason enough to at least talk about the basics, especially for younger readers of this blog.

So, I hope you find something useful for yourself in this issue, and otherwise, I want to wish you an excellent start to the coming week!

Best Regards,

– Martin from Deliberate-Diligence.com

Today at a Glance:

- 💬 Quotes about saving money

- 🧠 Mindset: Shifting from spending power to capital thinking for financial success

- 🥸 Opinion: When and how to invest in the stock market

- 📄 Fallacies: Avoiding 10 common fallacies that impact financial decision making

- ⚒️ Tools & Practices: The 50/30/20 rule, daily and monthly budgeting, Inflation-adjusted savings forecasts, investment portfolio balancing

💬 Quotes about saving money

At first, I had to think about Ernest Haskins' quote for a moment. What does he mean? The meaning is as follows: You read a lot of tips that say you should start small. "A penny saved is a penny earned". Or "Even a monthly investment savings plan of €25 can be enough". Or "It's enough to save 10% of your income."

I think this is a fallacy. Many people have much less purchasing power than they think because they overlook that they save too little money.

I save 25% of my income and think that is the lower limit of what I should do to build capital. And some people save only 2.5%, 5% or 10%. I think that's too little.

That's why I chose these quotes as the start of this newsletter issue: Choose a generous savings amount and immediately put it into a savings account or portfolio upon receiving your salary or income. It's important not to save what's left at the end of the month but only to spend what's left after setting aside the savings amount.

🧠 Mindset: Shifting from spending power to capital thinking for financial success

Before we talk about specific methods, I want to first write about a mindset error that I believe many people have.

I had it in my 20s, and it almost drove me to ruin. Two thinking errors were fatal in combination.

Thinking Error 1: Future Purchasing Power ≠ Current Purchasing Power

I was in my mid-20s and a well-educated computer scientist. News, media, and family told me that as a computer scientist, all doors would be open, and I wouldn't have to worry about finances. Although my starting salary in my first job was significantly lower than I had assumed, I still had deep confidence that my future self would earn much money. It may be true, maybe not, but the problem was that I didn't measure my purchasing power based on my current situation but on my hoped-for future.

The result? Thanks to generous credit cards, I spent more than I had because I assumed I could quickly pay it off in the future.

Of course, this is insane because salary increases in the following years were much more modest than I had assumed, and ultimately, interest rates ate up the salary increases.

It took me 7 years to compensate for the financial mistakes of my first 3 years in the workforce and pay off the debt. Those are 7 years that I didn't build my capital.

And all for consumption and avoidable expenses.

Thinking Error 2: Thinking in Purchasing Power and Not in Capital

The second mistake was that I considered monthly income as purchasing power by converting it into a monthly rate. That means that if I earned 100€ more monthly, I mentally automatically converted it into a potential loan (24x100€ = A purchase of 2400€).

If I paid off a loan, I didn't think, "Great, more free cash flow", but "Great, new purchase possible!".

Fortunately, I eventually - not too late - educated myself financially and learned what capital is. It's a word that everyone now says ("Yes, it's clear what capital is"). But properly internalising it is something else.

Nowadays, I associate an expectation of return with every euro of my income, no matter how small or large, that doesn't flow into necessary basic purchases. I expect it to earn me 7% or even 10% year after year (the exact amount of expectation doesn't matter, it's about the change in perspective). That means when I see a euro I have today, I expect it to be worth two euros in 7 years (= doubling time of 10% return).

It's challenging to convey this through a blog article. Still, when you associate a different expectation with the euros and see it as capital, it hurts to spend it on consumption. This pain in the purchase decision is vital because it leads to questioning purchases.

My Recommendations to You:

- Don't saddle your future self with debt. Don't overestimate their ability to pay off debt, even if you're on a steep career path.

- Engage with capital. Read about it. Invest and see how dividends and market growth can affect your finances. This will help you recognise what a missed opportunity it is to see money only as pure purchasing power.

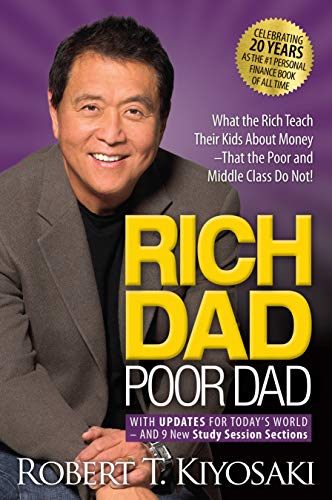

These two evergreen books could introduce some simple introductions to this mindset shift:

Rich Dad Poor Dad: What the Rich Teach Their Kids About Money That the Poor and Middle Class Do Not!

I was a bit sceptical because of this puffery title, but the content is good and transported as a narrative.

Think and Grow Rich

Another evergreen book about this fundamental mindset shift.

🥸 Opinion: When and how to invest in the stock market

I have friends who feel overwhelmed by the stock markets and the terms, chances, and risks involved, and therefore do not invest, even though they know they should.

But what's the alternative? The interest rates on accounts are insufficient to compensate for inflation, and most of us find real estate unaffordable.

So: Only ETFs and stock investments remain a feasible option.

Honestly, I would just get started. Get a Neo-Broker app (in Germany, for example, Trade Republic or Scalable Capital), register, and invest the first hundred euros monthly in popular stocks and ETFs.

Whether the market is rising or falling, the key is to get a feel for how investing in the market works. Especially if you start with broadly diversified ETFs, not much can go wrong.

But I wouldn't invest everything immediately if you have more considerable sums in your account. Instead, set up a standing order for an amount you feel comfortable with and where the damage isn't so significant if something goes wrong, and just get used to making stock and ETF purchase decisions once a month.

The performance history of my stock and ETF portfolio since 2019

Here is the curve of my investments to show that the exact market situation usually doesn't matter:

- Scenario A: The market is growing: You'll notice how market forces are increasing your capital. You'll learn how your market theses ("Hey, Company XYZ is great") and actual market performance correlate.

- Scenario B: The market is falling: Also great because if the market and the company stocks you own don't completely break, things will eventually go up again. Over long periods, there has always been a good average market return. Your losses may teach you more than any gains.

I only have one rule: I don't take money from my stock portfolio until I reach age. If I do anything, I rebalance (sell one stock and buy another if I no longer believe in a particular stock). This also ensured that I didn't panic and sell during the maximum drawdown you see on the chart. Because then I would have realised the loss and wouldn't have profited from the eventual upturn.

I want to tell you that even if you lose money because you choose the wrong ETFs or stocks, the learning you gain in the first few years of investing is worth much more than any potential gains or losses.

PS: I learned most of what I know through podcasts during my walks - maybe that's also an option for you as a source of knowledge?

📄 Fallacies: Avoiding 10 common fallacies that impact financial decision making

Financial decisions are critical to our lives, but it's easy to fall into common traps that can lead to regrettable choices. Here are 10 common fallacies to avoid when making financial decisions:

- Sunk Cost Fallacy: Occurs when we continue investing in something simply because we've already spent money on it. To avoid this, focus on future costs and benefits rather than past investments.

- Confirmation Bias: This tendency favours information that confirms our preconceptions. Always seek out diverse sources of information and challenge your assumptions to make better financial decisions.

- Anchoring Bias: This occurs when we rely too heavily on an initial piece of information, like a stock's initial value, to make decisions. To avoid this, consider multiple sources of information before making a choice.

- Recency Bias: This is the tendency to weigh recent events more heavily than older ones. Remember that short-term market fluctuations are normal and focus on long-term trends instead.

- Hindsight Bias: This is the belief that past events were predictable. Avoid this by acknowledging the unpredictability of the market and making decisions based on current information.

- Overconfidence: Overestimating your knowledge or abilities can lead to poor financial decisions. Remain humble and accept that you don't know everything; seek expert advice when needed.

- Herd Mentality: Following the crowd can lead to irrational decision-making. Do your own research and choose based on your needs and goals.

- Loss Aversion: This is the tendency to avoid losses more than seek gains. Remember that risk is a natural part of investing, and accept that some losses are inevitable to achieve long-term gains.

- Mental Accounting: This refers to treating different types of money differently, such as being more cautious with hard-earned money than "found" money. To avoid this, treat all money equally and consider your financial goals.

- Gambler's Fallacy: This is the belief that past events can predict future ones, like thinking a coin toss will be tails after several heads in a row. In financial decisions, remember that past performance does not indicate future results.

Here are three great books that can help you learn more about fallacies and improve your critical thinking skills:

- "The Art of Thinking Clearly" by Rolf Dobelli: This best-selling book explores various cognitive biases and fallacies that can impact our decision-making. Dobelli provides clear explanations and real-life examples to help readers understand and avoid these common pitfalls.

- "Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman: Written by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, this book delves into the two systems that drive our thought processes: the fast, intuitive, and emotional System 1 and the slow, deliberate, and logical System 2. Kahneman discusses various cognitive biases and fallacies that stem from these systems, helping readers improve their decision-making abilities.

- "You Are Not So Smart" by David McRaney: This engaging and accessible book covers many cognitive biases, heuristics, and fallacies that impact our daily lives. McRaney's conversational style and anecdotes make complex psychological concepts easy to understand, allowing readers to recognise and overcome these mental pitfalls.

These three books provide valuable insights into the various fallacies and cognitive biases that can influence our thinking and decision-making.

⚒️ Tools & Practices

In this chapter, I'll briefly describe the tools I use to ensure my financial stability.

The "50/30/20 rule

The "50/30/20 rule" is a popular budgeting technique that helps individuals create a balanced financial plan by allocating their income into three categories: needs, wants, and savings or investments. Following this simple rule, people can prioritise their expenses, ensuring they cover essential costs while still enjoying life and preparing for the future. This budgeting approach promotes financial stability and encourages individuals to take control of their economic well-being and develop healthy money management habits.

Under the "50/30/20 rule,"

- 50% of one's income should cover essential needs like housing, utilities, groceries, and transportation. By limiting these necessary expenses to half of one's income, individuals can ensure that their basic needs are met without sacrificing financial stability. Additionally, this allocation strategy helps people differentiate between their actual needs and desires, leading to more mindful spending and ultimately resulting in long-term financial benefits.

- The remaining income is divided between wants and savings or investments, with 30% going towards discretionary spending and 20% dedicated to building financial security.

This allocation allows individuals to indulge in non-essential expenses, such as dining out, vacations, or hobbies, without compromising their long-term financial goals.

By setting aside 20% of their income for savings and investments, individuals can work towards building an emergency fund, saving for retirement, or investing in their future.

Regardless of the category (Need/Want), I would ensure that you do not have more than 30% of your income tied up as fixed monthly expenses.

Why? Because otherwise, you lack the flexibility to make decisions within a month according to needs and situations. With too many contracts, you take the air to breathe.

Monthly Budgeting

To implement the 50/30/20 rule, it is a good idea to structure your finances with a monthly budget. This means you think about your budget pots (rent, travel, entertainment, learning, ...) and assign a monthly budget to each pot.

During the month, you review your expenses weekly and subtract them from the pots. If a pot has no money left, you can't spend any more money there.

Regarding tool support, you have three options:

- Build it yourself in Excel/Google Sheets

- A budget app where you have to enter your expenses manually.

- A budget app which automatically draws the payments from your accounts and classifies them.

I use a combination of 2+3 for my budgeting, and I make it a point to manually review all of them at least once a week. This helps me identify, for instance, any Amazon expenses that may have slipped under my radar during the week but add up to a significant amount over time. By consciously reviewing my expenses, I can become more aware of them in the future.

With an app that does everything automatically, you only have this effect to a limited extent.

Daily Budgeting

Monthly budgets are excellent and valuable but sometimes too abstract.

What is very concrete, on the other hand, is a daily budget. This works in such a way that you divide the variable expenses, which you deduct after all savings and fixed costs, by the number of days in a month, and thus know, for example, that you should only spend 20 euros per day.

In terms of mindset, this means you pay yourself an allowance daily. If you spend more today, you can spend less tomorrow. A fair deal!

You can track this in Excel/Google sheets or use a Daily Budgeting app on your phone that will help you keep track of things.

On iOS, for instance, I like this app the most:

Track your Investment Portfolio

Savings Forecasting

The last thing I want to suggest is to consider how much you need to save.

You can make a calculation for yourself like the following:

- Determine your retirement goal: You want to supplement your state pension by €1,500 per month in today's money 30 years from now.

- Account for inflation: Assuming an annual inflation rate of 3%, the €1,500 you need today will be equivalent to €3,600 per month in 30 years.

- Calculate the annual amount: To determine how much you need per year, multiply the monthly amount by 12 (€3,600 * 12 = €43,200).

- Estimate the return on investment: Assuming your savings will generate a 7% return, you'll want to have enough capital to provide €43,200 per year without touching the principal.

- Calculate the required capital: To determine how much capital you'll need, divide the annual amount by the expected return (€43,200 / 0.07 = €617,143).

So, to achieve your goal, you should aim to have €617,143 saved up by the time you reach 67 years old, in addition to your state pension.

This is difficult to achieve for many incomes, and it means that you then still have two evasive manoeuvres:

- You could instead focus on reducing spending as much as possible in retirement (work on the management of your expectations)

- Accept that, at some point, you will have to consume the capital stock yourself when you get old.

That's it for this Diligent Sunday! I hope this issue was in some way helpful to you.

Feel free to add tips and thoughts to this page's comment section, Twitter or LinkedIn!

Best regards,

-- Martin from Deliberate-Diligence.com

Discussion